In the late 1950s, around the same time George Brecht devised his first event scores, Allan Kaprow (American, 1926–2006) developed the “happening.” Kaprow had started out as a painter and then, in the tradition of Cubism and Dada, began to affix everyday materials to his paintings. Inspired by Jackson Pollock’s mural-size paintings and lowbrow funhouses alike, Kaprow’s work rapidly increased in scale from collages, to three-dimensional assemblages, and finally to room-size installations he termed “environments.”[1] Kaprow constructed environments out of a signature array of everyday objects (plastic drop cloths, Christmas lights, tinfoil, mirrors). In happenings, he incorporated human participants, and gave them various actions, tasks, and games to perform.

While Kaprow staged several early happenings in art galleries, he soon decided that the physical, psychological, and social coordinates of the gallery impeded the sort of participation he desired from viewers. He thus began to work in a way we would now call site-specific, meaning that he created happenings for specific non-art locations and structures. Another major shift in the poetics of the happening occurred around 1965 when Kaprow decided to “eliminate the audience” (as he put it) by working exclusively with small groups of committed participants to realize a given happening over two or more days.[2] Kaprow fostered such intimacy in order to differentiate the happening from both traditional theater and youth culture (light shows, rock concerts, promotional stunts), and their purportedly more passive forms of spectatorship. In part, he was responding to the fact that the word “happening” had become synonymous with spectacular events—whereas before 1965 it meant simply “occurrence.” For this reason, Kaprow abandoned the word “happening” altogether in 1968 and made what he called “activities” for the rest of his career.[3]

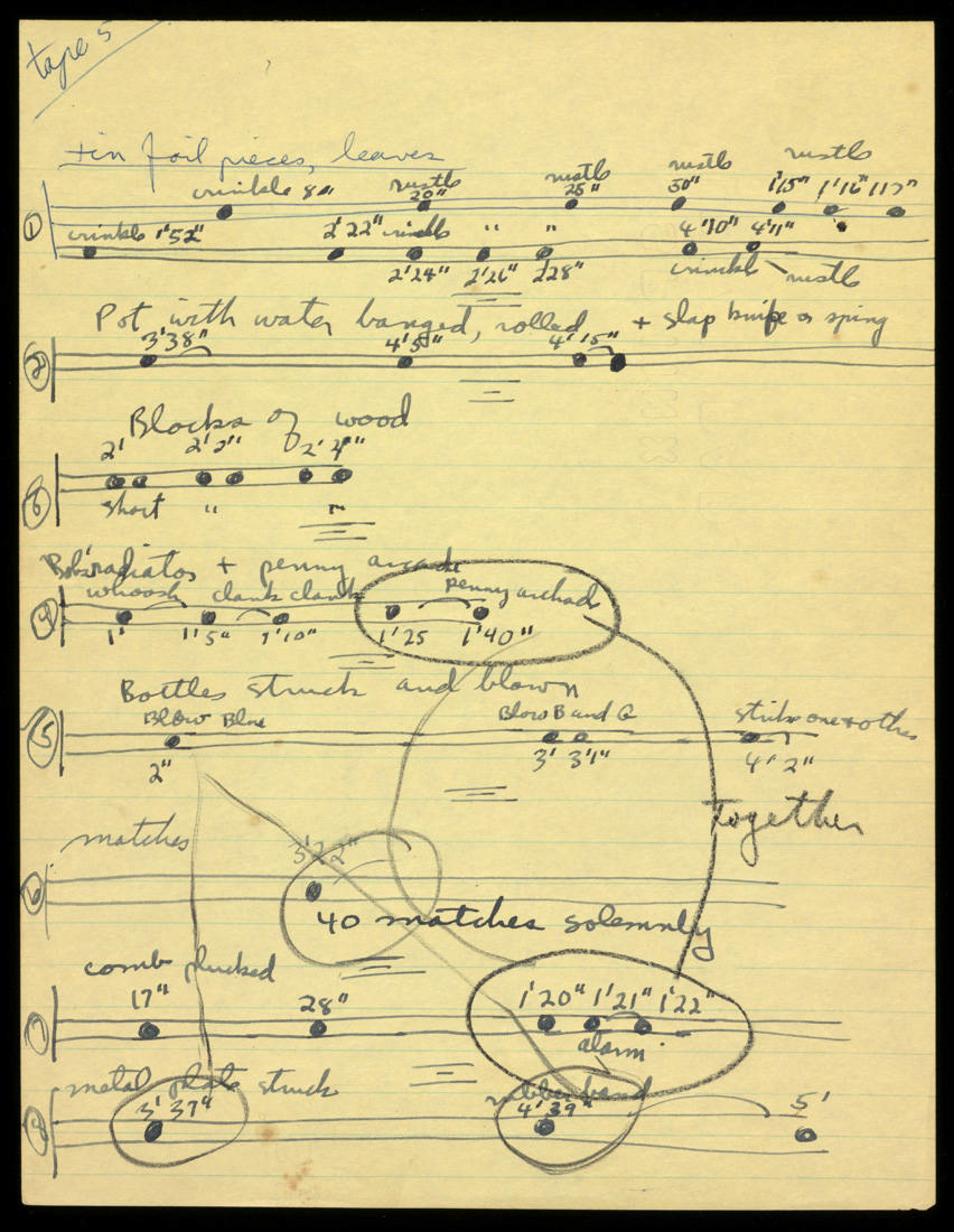

Kaprow developed a notation practice to support his work with happenings and activities. Like Brecht he was profoundly influenced by John Cage’s “Experimental Composition” course at the New School for Social Research (fig. 1). By the time Kaprow entered Cage’s class in late 1957, he had already experimented with sound in his assemblages and environments, notably via mechanical toys and sound collages on magnetic tape (fig. 2).[4] Cage’s course deepened Kaprow’s interest in sound, but the most important lesson for Kaprow concerned indeterminacy. Cage taught that the score and its performance are at once interdependent and incommensurate: where the score is abstract, the performance is concrete; where the score is fixed, every performance is different. And, in the context of his course, Cage did so in a fun and participatory way: in the typical class he had students introduce and perform a score they had composed quickly at home, and then the whole group would analyze what had happened—and the relationship between what had happened and the original form of the score.[5]

Kaprow’s activities can be seen to revisit the sort of unrehearsed performance and philosophical discussion that flourished in Cage’s classroom, and of the activities Routine is a prime example. Commissioned by the Portland Center for the Visual Arts (PCVA) in April 1973, Routine encompasses several interlocking elements. In the fall of 1973, Kaprow composed the score, which he referred to as the “program.”[6] During a three-day residency in December, Kaprow then realized the program with twenty or so different pairs of participants. The realizations took place on a Saturday afternoon, and were bookended by a “briefing” on Friday evening and a “review” on the Saturday evening. During his remaining available time on Friday and Sunday, Kaprow produced a version of Routine in the form of a short instructional film. Finally, two years later, Kaprow published Routine as an “activity booklet,” which included the program, photographs, and an accompanying essay.

Over the course of Routine’s five parts, Kaprow uses ordinary objects to isolate and scramble visual and aural communication channels. In parts one, three, and five, the two participants look at one another in mirrors; in parts two, four, and five, they speak over the phone. In each part, participants alternate and repeat routine gestures and phrases to the point of illegibility, inaudibility, or exhaustion, and they interact with one another in both intimate and socially awkward ways. Over the course of each part, communication becomes more and more difficult, while the various tasks become further abstracted, inducing moments of self-conscious reflection.

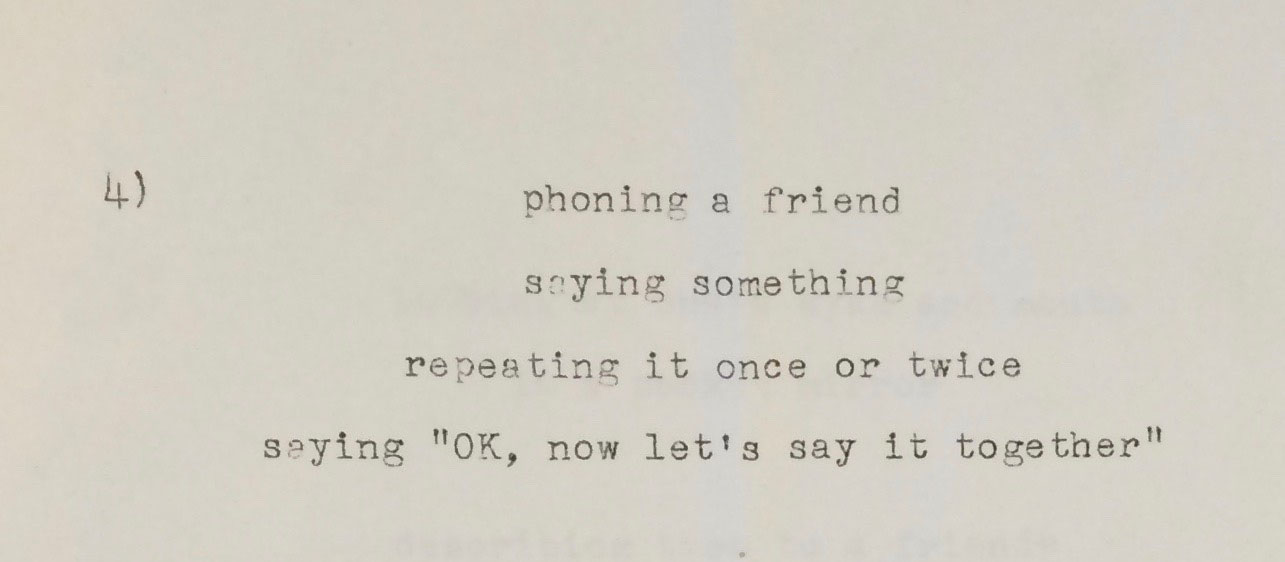

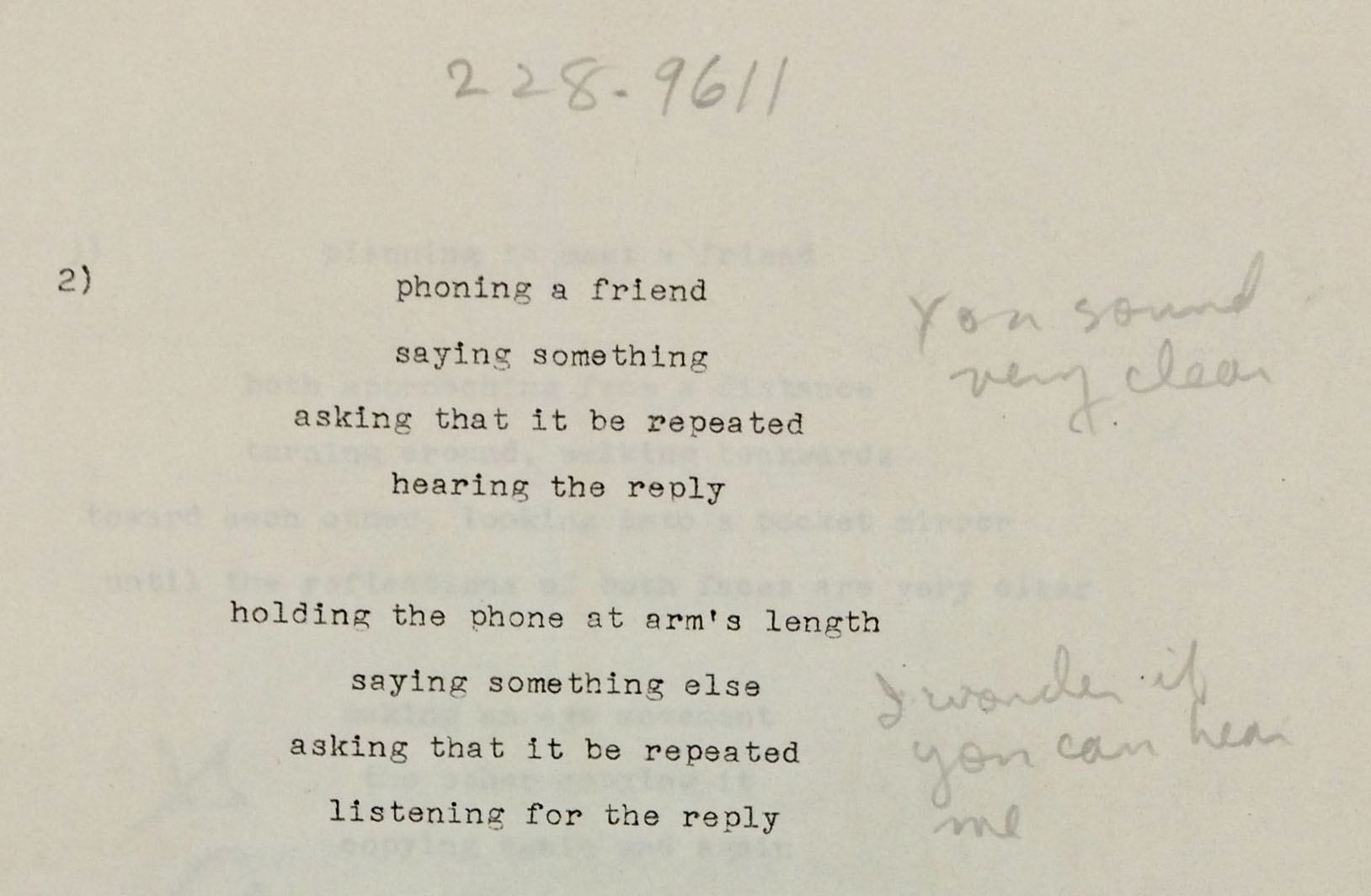

Kaprow’s program is composed of ordinary language, but re-purposed in highly formal ways. The blocks of text are centered, symmetrical, and generously framed by blank space. Most importantly, Kaprow writes in the continuous present tense, rather than the imperative. This is unusual for instructions and to some extent lends the program a self-contained, poetic quality. At the same time however, many of the notations are indeterminate and thus require considerable interpretive work to be realized, for example the beginning of part 4 (fig. 3). “Saying something”—but saying what exactly? This is for the performer to decide. Kaprow’s intense focus on the form of the phone call, seemingly at the expense of its content or message, invites comparison to Brecht’s earlier Three Telephone Events (1961), an event score that Kaprow particularly liked (fig. 4).

Kaprow maintained that his experimental scores should not circulate independently of a structured pedagogical context—a conceit that distinguishes his practice from that of Brecht and other Fluxus artists.[7] It may also reflect his long career as a university professor.[8] Kaprow argued that, “An unfamiliar genre like this one does not speak for itself. Explaining, reading, thinking, doing, feeling, reviewing, and thinking again are commingled.” [9] To this end, Kaprow introduced Routine with a briefing—a short lecture that broke down the formal structure of the activity and sketched out various ways to interpret it. Here, Kaprow translated philosophical questions into vernacular terms, and made the activity sound both intellectually worthwhile and fun. It was with a certain seriousness of purpose, then, that the participants in Routine spread out across Portland to realize the program in their own ways (fig. 5). After the realizations had occurred, Kaprow reconvened the participants at the PCVA for a review—a seminar-style discussion where participants analyzed their experiences. Did your experience of Routine conform to your expectations? How did your experience differ from your partner’s? Questions such as these enabled Kaprow to gather crucial feedback, and to measure, however informally, the productivity of the program—its ability to inspire diverse realizations while maintaining a unified purposiveness.

Kaprow’s commitment to framing his activities pedagogically created certain challenges, particularly with regard to publication. The typed program alone did not offer enough guidance in Kaprow’s view, so he developed two novel publication formats: the activity booklet and the activity film. The activity booklets invariably begin with a short essay that condenses the functions of briefing and review. Here, Kaprow clarifies the key concepts that animate the program and summarizes the range of realizations that have already occurred. But even this was not enough to reel in the distant reader. In order to provoke physical response, Kaprow enlisted the mimetic magic of photographic media. As he explained at the start of the Routine activity booklet,

The photos here do not document ROUTINE. They fictionalize it. They were made and assembled to illustrate a framework of moves upon which an action or set of actions could be based. They function somewhere between the artifice of a Hollywood movie and an instruction manual.[10]

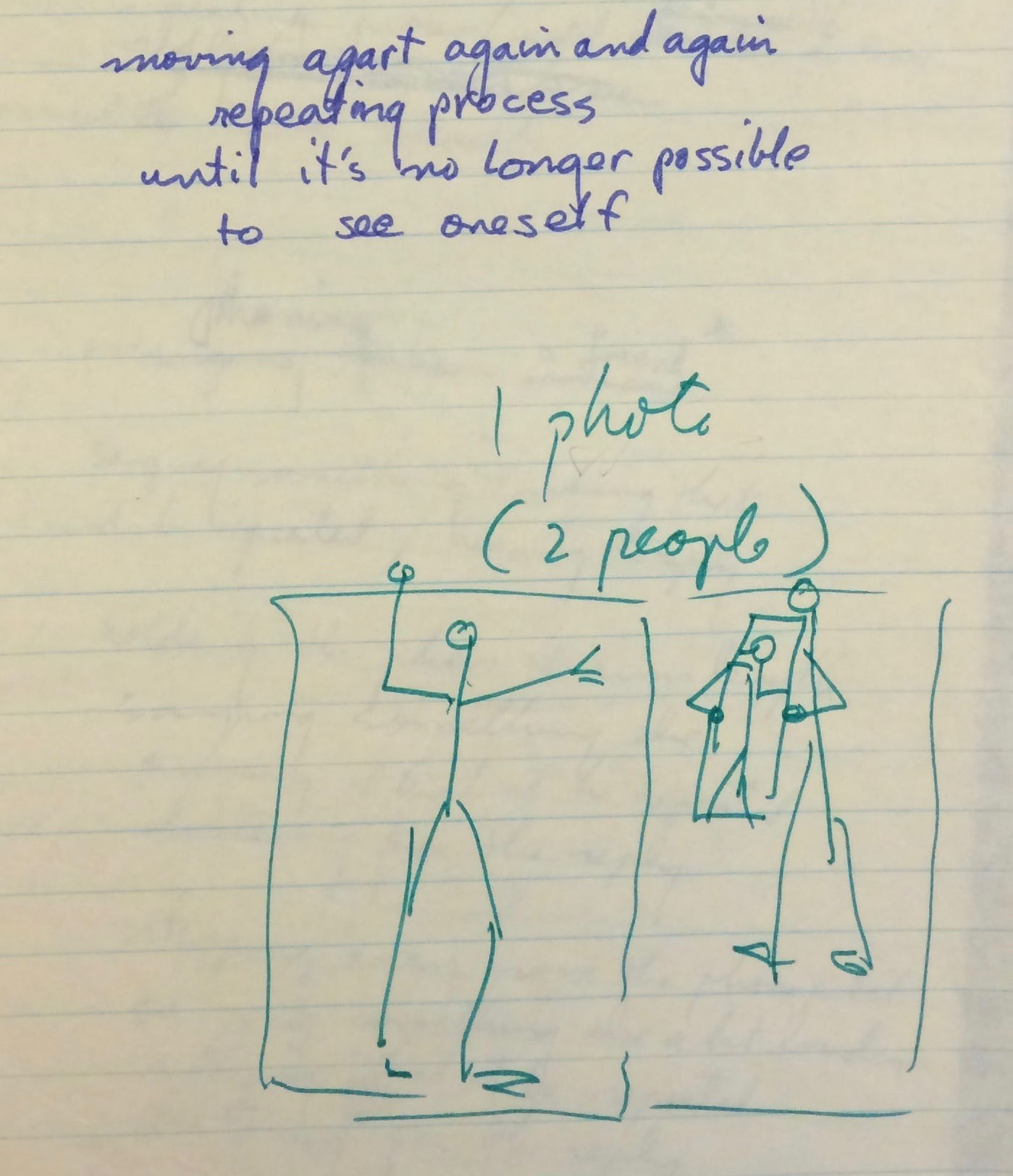

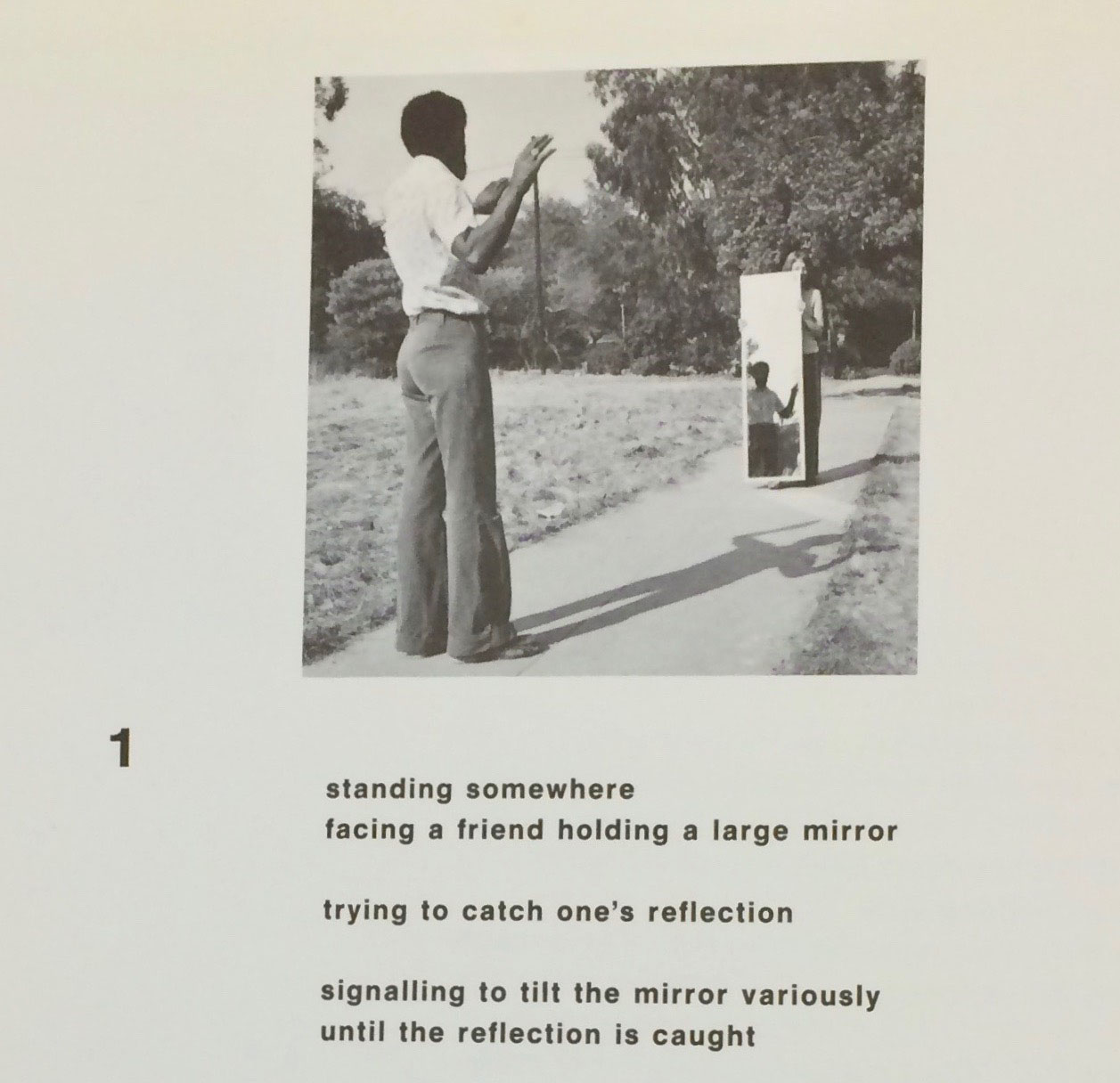

Where most artists in Kaprow’s milieu used photography to document performances, Kaprow used the medium to inspire new ones. To this end, he developed a diagrammatic approach that began with his sketching out the basic photographic compositions in advance. More than merely a guide, these sketches yielded photographs that retain a strong graphic quality: individual faces are deliberately obscured in favor of clear postures and spatial relationships. For example, on the first page of Routine, the man’s shadow is a stick figure come to life, or rather a living person made into a stick figure (figs. 6 and 7). [DES: Please pair figs. 6, 7.] Sometimes Kaprow took the photographs for his activity booklets, but more often he directed an art student to do it, in this case a student of his at Cal Arts (Alvin Comiter). Nevertheless, it was Kaprow who dictated the style as well as the mise-en-scène, acting like a film director vis-à-vis his cinematographer.

The PCVA gave Kaprow a modest budget for documentation. But instead of filming the Saturday realizations as one might expect, Kaprow kept those private. He had determined that the presence of a camera altered the experience of performance in profound ways that had to be carefully accounted for. He thus diverted the funds to produce an instructional film, complete with copious voiceovers, intertitles, and semi-rehearsed performances. Like the sort of industrial film it mimics rhetorically, Routine was made cheaply and quickly (fig. 8). Kaprow engaged the technical expertise of young people to carry out his vision, namely an aspiring documentary filmmaker (Michael Sullivan) (fig. 9).[11]

The film Routine follows the pattern of the genre of the activity booklet in many ways. The compositions and gestures tend to look somewhat abstract, thanks in part to the readymade geometries of the locations themselves, like the white grid of the parking lot (fig. 10). Moreover, the shot-reverse-shot editing is easy to follow and familiar from classical Hollywood film grammar. It shows that Kaprow’s numerous activities for couples frequently entail an exaggerated series of miscommunications and awkward entanglements that curiously parallel the plot of a romantic comedy.

Kaprow’s films and videos of the 1970s were experiments. He was clear about their intended function—to serve as animated, yet indeterminate scores, rather than performance documents. Indeed, Kaprow stated this intention directly through his consistent opening voiceovers (figs. 11-14). [DES: Please group figs. 11, 12, 13, 14 in a grid.] But Kaprow was not entirely sure that any film could function as an indeterminate score, since participants might be tempted to simply mimic what they saw on screen, thus apparently foreclosing the creative aspect of realization in the Cagean tradition. In characteristic fashion, Kaprow devised a further experiment in 1976. He directed a group of friends to use one of his instructional videotapes as a score, and then he asked them about it in a review (fig. 15). As it turned out, most of them complained about the videotape—it was idealized, didactic, or otherwise misleading. Where most artists might find this reaction disappointing, Kaprow was pleased. For him, the score was at least in part a tool for generating meaningful debate and self critique. The process of realization would ideally generate new forms, which is precisely what happens on the tape when one of the participants imagines an almost absurdly recursive instructional videotape about how to watch instructional videotapes.

Emily Ruth Capper

Lecturer, Departments of Art History and of Cultural Studies and Comparative Literature

University of Minnesota

Further reading:

Jonathan Furmanski, “The Allan Kaprow Papers: Video before Then,” Getty Research Journal, No. 1 (2009), pp. 205-210.

Allan Kaprow, Essays on the Blurring of Art and Life, ed. Jeff Kelley (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003).

Jeff Kelley, Childsplay: The Art of Allan Kaprow (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004).

André Lepecki, “Redoing 18 Happenings in 6 Parts.” In Allan Kaprow—18 Happenings in 6 Parts— 9/10/11 November 2006 (Göttingen: Steidl Hauser & Wirth, 2007).

Glenn Phillips, “Time Pieces,” in Allan Kaprow: Art as Life, ed. Eva Meyer-Hermann, Andrew Perchuk, and Stephanie Rosenthal (Los Angeles: Getty Research Institute, 2008).

Miwon Kwon, One Place After Another: Site-Specific Art and Locational Identity (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2004).

Howard Singerman, Art Subjects: Making Artists in the American University (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999).

Judith F. Rodenbeck, Radical Prototypes: Allan Kaprow and the Invention of Happenings (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2011).

Philip Ursprung, Allan Kaprow, Robert Smithson, and the Limits to Art, trans. Fiona Elliott (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2013).

Eric Padraic Morrill, “What can we learn from photographs of Happenings?: Allan Kaprow’s Transfer,” Media Archive Performance, No. 5 (June 2014), accessed at > http://www.perfomap.de/map5/paradoxe-medien/what-can-we-learn-from-photographs-of-happenings-allan-kaprows-transfer

Allan Kaprow, “The Legacy of Jackson Pollock” (1958), in idem, Essays on the Blurring of Art and Life, ed. Jeff Kelley (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003), 1–9. Kaprow, Assemblages, Environments, and Happenings (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1966), 157–165. ↩︎

Kaprow, “Nontheatrical Performance” (1976), in idem, Essays on the Blurring of Art and Life, 173. ↩︎

In his proto-activity booklet for the activity Loss (1973), Kaprow explains: “my choice of the word ‘Happening’ was intended to neutralize art and to suggest the possibility of a consciousness and mode of action unencumbered by associations with either any art or other profession. Once I saw that it acquired stereotypical meanings which only got in the way of that consciousness, I adopted Michael Kirby’s word ‘Activity’ as an alternative.” Kaprow, “Easy Activity,” 177. [Full publication info. TK.] Allan Kaprow Papers, ca. 1940–1997 (980063), box 20, folder 13, Los Angeles, Getty Research Institute. Michael Kirby was a drama professor at New York University, and the editor of Happenings: An Illustrated Anthology (New York: E.P. Dutton & Co., 1965). ↩︎

Joseph Jacobs, “Crashing New York à la John Cage,” in Off Limits: Rutgers University and the Avant-Garde, 1957–63 (Rutgers: Rutgers University Press, 1999), 97. ↩︎

Cage recalled about his New School course: “One thing I insisted upon in the class, I said, ‘Don’t bring any work to the class that you can’t do. If you can’t do it here, don’t bring it here.’” Oral history interview with John Cage, 1974 May 2, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington D.C., accessed at http://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/interviews/oral-history-interview-john-cage-12442. Kaprow in conversation with Gordon Mumma, James Tenney, Christian Wolff, Alvin Curran, and Maryanne Amacher, “Cage’s Influence: A Panel Discussion,” in Writings through John Cage’s Music, Poetry, and Art, ed. David W. Bernstein and Christopher Hatch (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2001), 169–71. The best-researched accounts of Cage’s pedagogy are in dissertations, as yet unpublished: Jeffrey Saletnik, “Pedagogy, Modernism, and Medium Specificity: The Bauhaus and John Cage” (PhD Diss., University of Chicago, 2009), and Rebecca Y. Kim, “In No Uncertain Musical Terms: The Cultural Politics of John Cage’s Indeterminacy” (PhD Diss., Columbia University, 2008). ↩︎

Kaprow called his scores “programs” after 1968, in order to make them sound less artsy and more like computers and communications systems. See Kaprow, interview with Richard Schechner, The Drama Review 12, 3 (Spring, 1968): 153; and idem, “Education of the Un-Artist, Part I” (1971), in idem, Essays on the Blurring of Art and Life, 106. ↩︎

Kaprow collaborated with many Fluxus artists over the years but he did not identify as a Fluxus artist. According to his account, this was because he could not get along with George Maciunus. Kaprow, “Maestro Maciunus” (1996), in idem, Essays on the Blurring of Art and Life, 243–246. ↩︎

Having earned a master’s degree in art history from Columbia University in 1952, Kaprow held academic posts at the following institutions: Rutgers University, 1952-1961; Stony Brook University, 1961-1969; California Institute of the Arts, 1969-1974; and University of California San Diego, 1974-1992. ↩︎

Kaprow, “Nontheatrical Performance,” 167. ↩︎

Kaprow, Routine, 1975. ↩︎

Brian Marquard, “Michael Sullivan; at 67, producer for ‘Frontline,’” The Boston Globe, June 28, 2013. Accessed at https://www.bostonglobe.com/metro/2013/06/27/michael-sullivan-marblehead-frontline-producer-projects-included-the-mormons-and-kind-hearted-woman/gsv1MiSnWgjxyJYJ0vkE8H/story.html. ↩︎