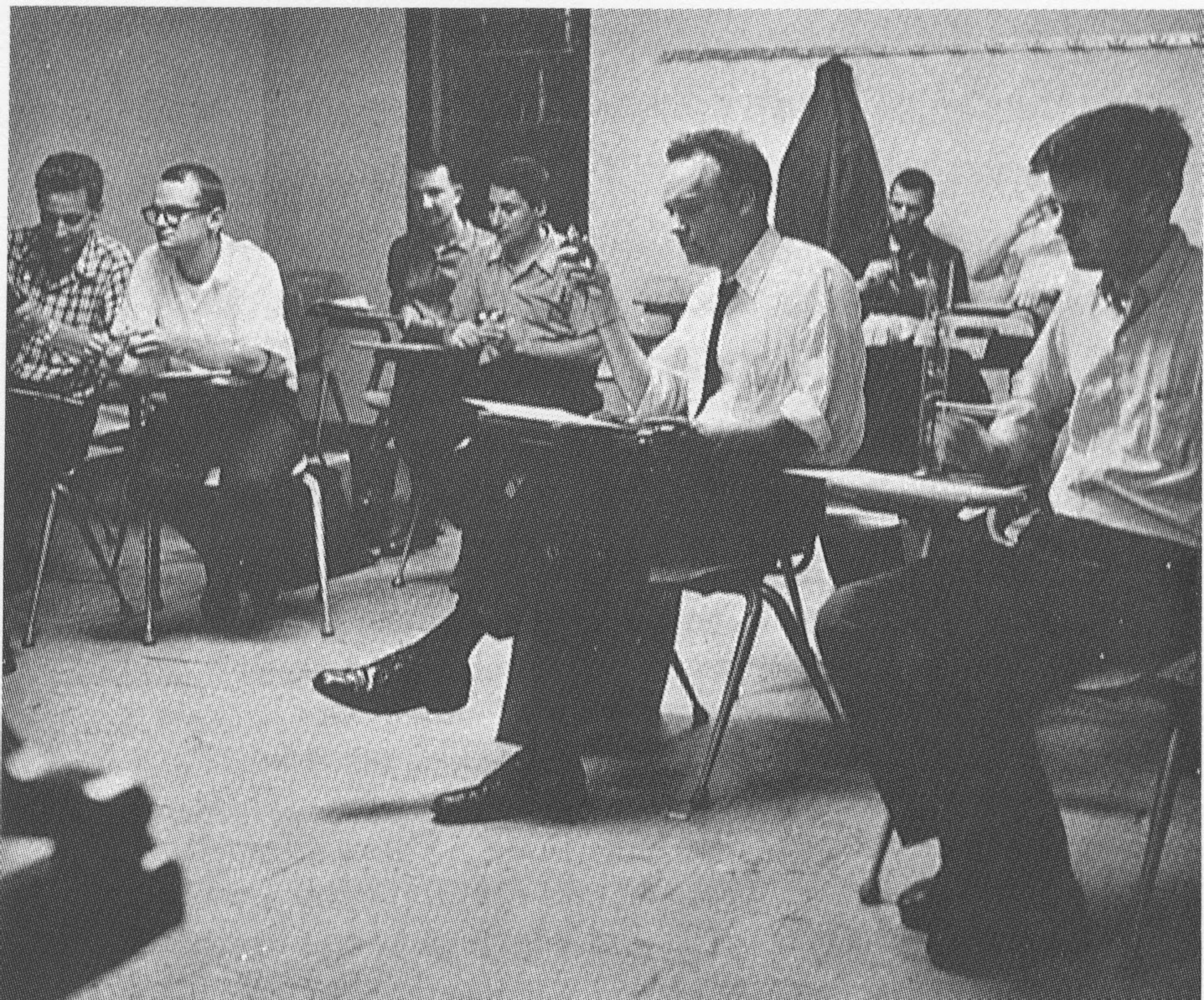

In 1959, in the wake of nearly a decade of experimentation with new forms of musical notation by composers in Western Europe and the United States, the American visual artist George Brecht began to develop a genre of text-based performance instruction he called the event score. Having turned his creative energies away from Abstract Expressionist painting and his intellectual focus from Jackson Pollock to John Cage, Brecht joined Cage’s experimental composition course at the New School for Social Research in the summers of 1958 and 1959. His notebooks from the time, selections of which are included in the Archive section of this chapter, provide an illuminating chronicle of this period. In the first pages of his notebook from the summer 1958 class, Brecht records Cage’s description of “Events in sound-space,” positing at the course’s outset an expanded field of music inclusive of all manner of multisensorial phenomena.[1] With this definition in place, Cage’s class became an important crucible for emergent intermedia practices. There, new musical thinking was further developed by a younger generation of composers, poets, and visual artists including Brecht, Allan Kaprow, Jackson Mac Low, Al Hansen, Dick Higgins, Toshi Ichiyanagi, Richard Maxfield, and Yoko Ono. Honed under Cage’s influence, Brecht’s event score became a major genre within Fluxus, the international artist collective founded in 1962 by George Maciunas, and with which Brecht aligned himself. Brecht’s scores were frequently included in Fluxus concerts, and hundreds of Fluxus scores were written after his model. While particularly influential and broadly circulated, Brecht’s scores were not singular. La Monte Young and Yoko Ono also composed text scores beginning in the early 1960s. Because of its incredible flexibility and potential for transmission across disciplines and practices, the event score has remained a useful format for myriad conceptual, performative, and process-oriented practices from the 1960s to the present.

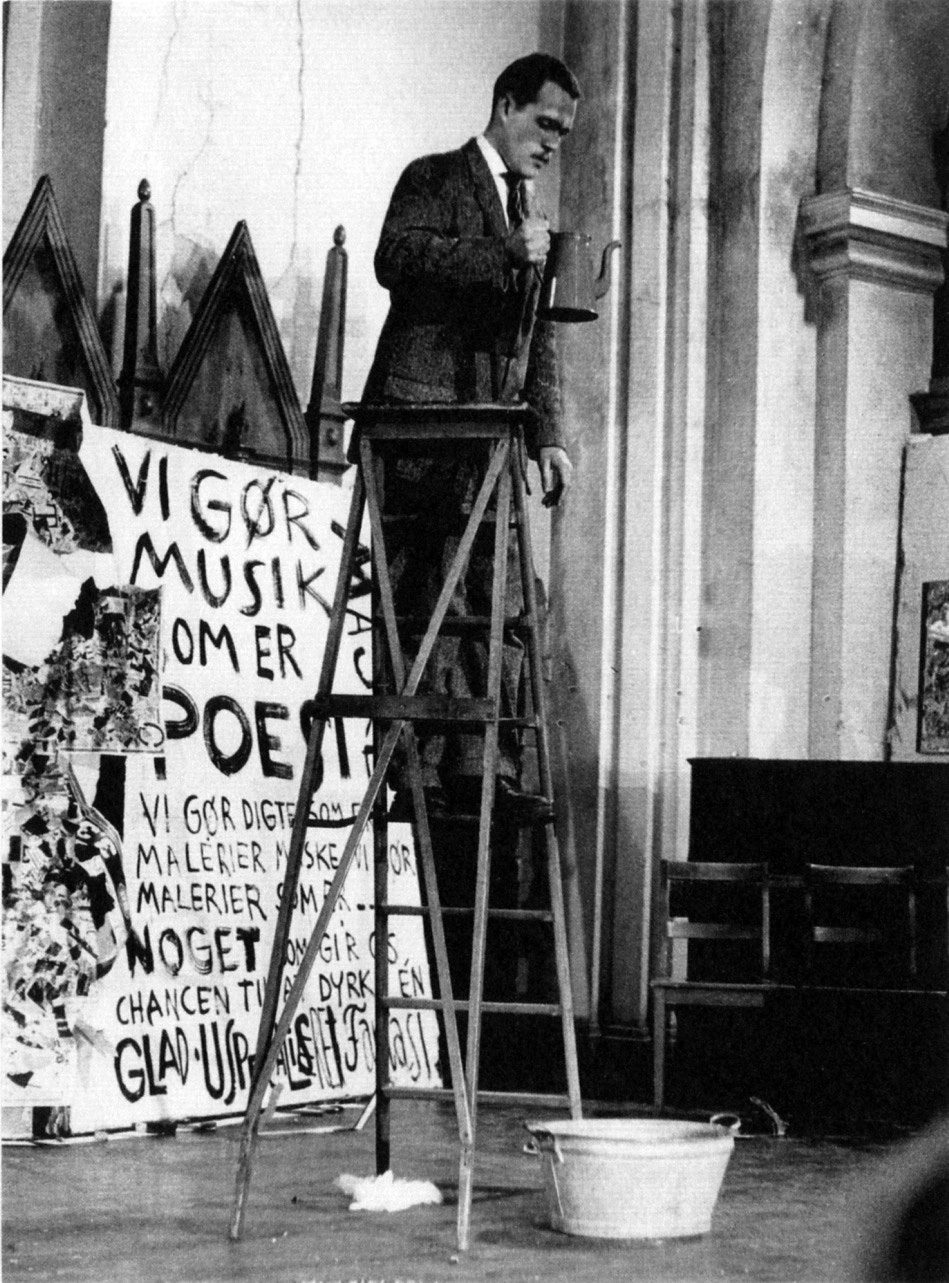

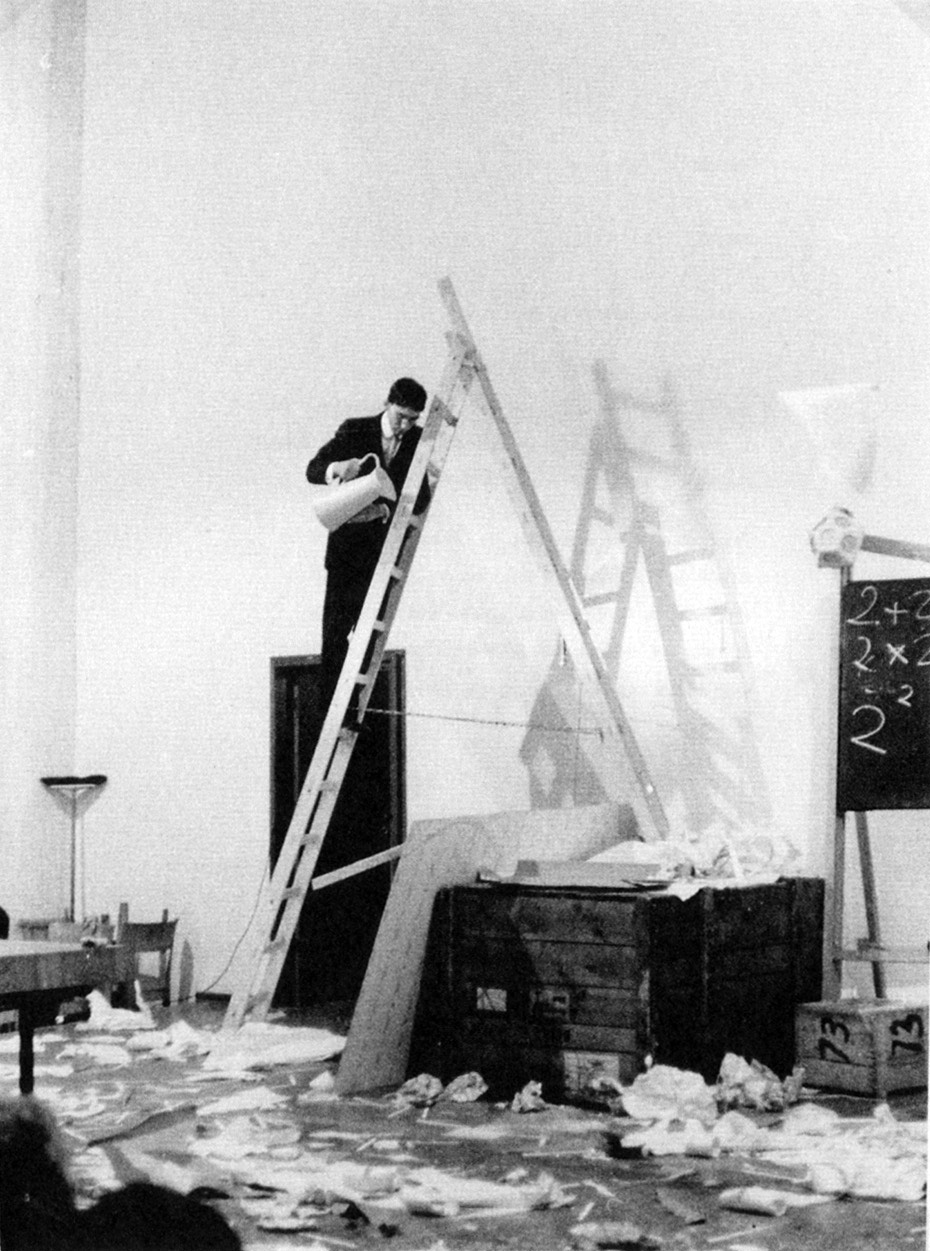

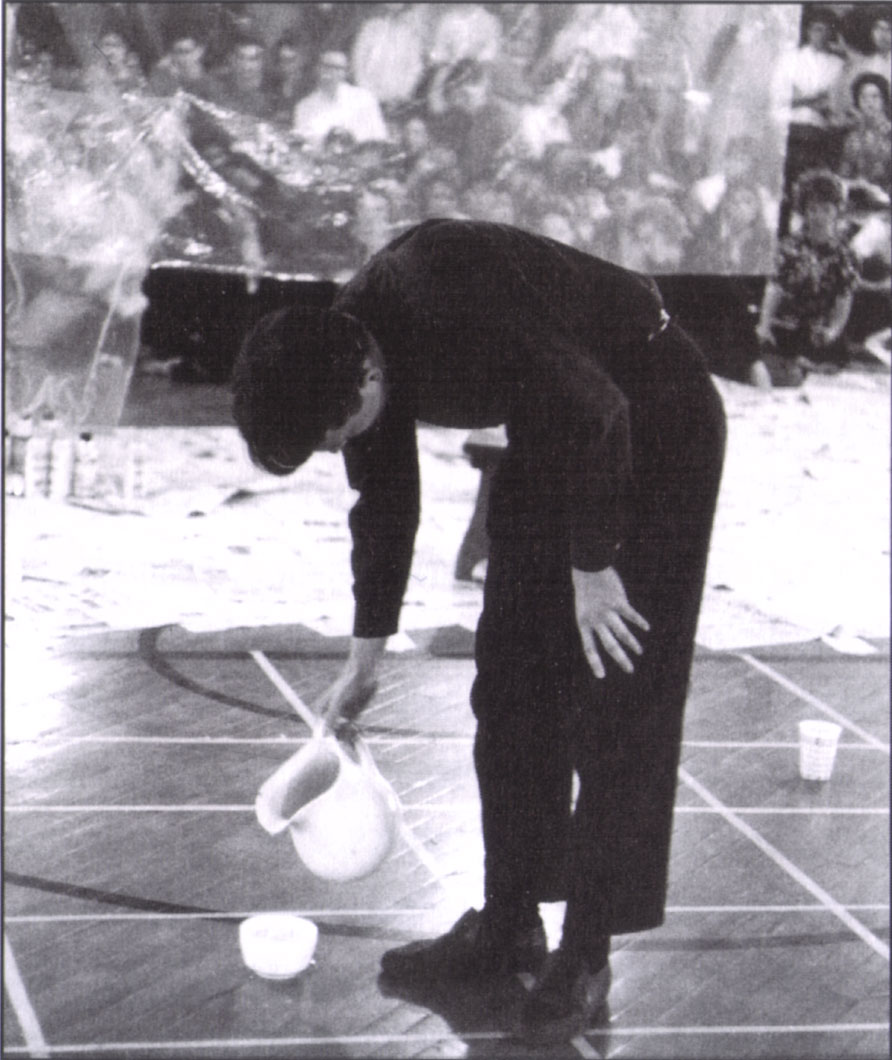

Among the dozens of event scores Brecht composed between 1959 and 1963, his Drip Music (Drip Event) (1959-1962) remains among the best known and is highlighted in this chapter as representative of the genre. Drip Music was performed regularly during the first Fluxus concert tour through Europe in 1962-1963 and became known mainly through the interpretations of others, since Brecht did not travel to participate in any of those concerts. Beginning with realizations of the piece by Dick Higgins in Copenhagen and George Maciunas in Dusseldorf, a performance convention developed wherein a single performer climbs a ladder and pours water from a pitcher into a vessel (sometimes amplified by contact microphone) placed on the floor below. This version of the piece continues to be performed today, as this chapter’s Playback section shows. Yet there have been many other versions too, including several offered by Brecht, suggesting that the artist wanted to keep the work perpetually open for rethinking. At Rutgers University in spring 1963, Brecht stood at floor-level and performed his drip in a modest, undramatic way, and in the 1970s he created a dripping faucet sculpture for the garden of the German collector and multiples publisher Wolfgang Feelisch. In contrast with Cage, who preferred his scores to be performed by approved collaborators like David Tudor (and who fought with uncooperative performers), Brecht said of his scores, “It’s implicit in the scores that any realisation is feasible….Any and every. I wouldn’t refuse any realisations.”[2] Brecht’s own interpretations of Drip Music are not to be taken as master examples to copy, and they do not exhaust the score’s possibilities for interpretation. Rather, the primary text that is Drip Music instigates the endless deferral of the work’s meaning, in an aesthetic gesture that anticipates postmodern critiques of the author and of the metaphysics of presence posited by cultural theorists including Michel Foucault, Roland Barthes, and Umberto Eco. Individual performances of an event score participate in an ongoing revelation of the score’s proposed form—actions and objects joined in a certain spatiotemporal arrangement—that remains always partially latent or potential.

As seen in the example of Drip Music, Brecht’s event scores are typically brief texts written in generic, open-ended language that opens up broad possibilities for performance and experience through its precise imprecision and careful attention to material relations and processes. The Brechtian event score describes a flexible structure that can accommodate an extraordinary range of content while maintaining the sparest continuity of identity. It forms the basis of a work that is, as Brecht described, “left as open as it could be and still have some shape.”[3] Individual performances of an event score may look or sound very different from one to the next. Yet one can observe a morphological continuity of activity across realizations, pointing to Fluxus’s radical rethinking of aesthetic form in terms of a mobile structure that exceeds the apparently visual and exists rather at the level of performed relations and processes.

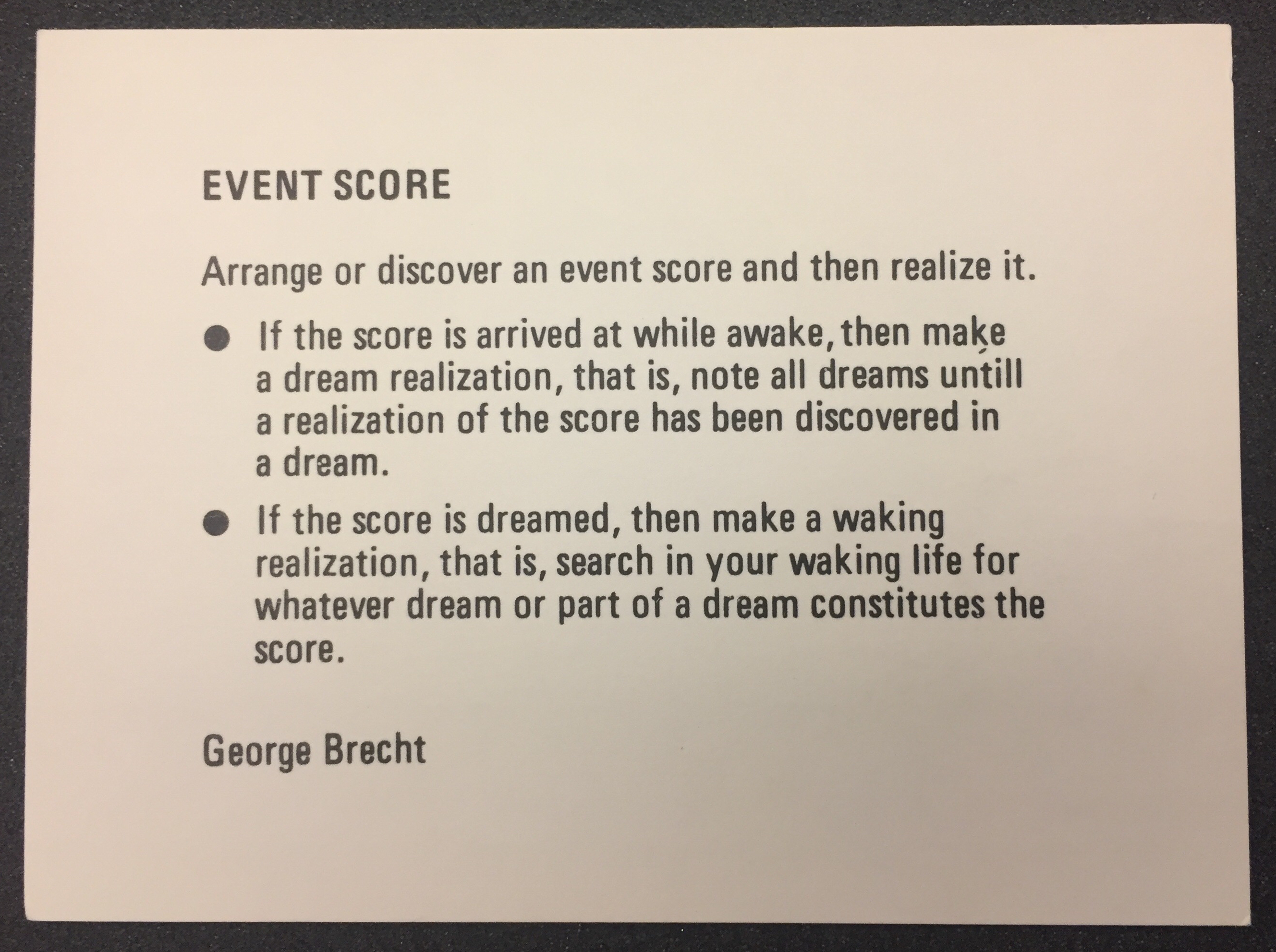

Remarkably, the language of Brecht’s event scores can suggest a performative response that is quite internal or passive, at times merely observational. George Maciunas called the scores “temporal readymades,” with the understanding that they often work simply to frame preexisting phenomena as being worthy of aesthetic consideration.[4] Accordingly, art historian Julia Robinson has argued that Brecht’s scores provide an indexical “interpretive matrix” that mediates our experience of quotidian phenomena whether performed or found, thus transforming our experience of the everyday. For example, Drip Music inverts ordinary associations in that, as Brecht noted, “the score calls attention to the fact that water dripping can be very beautiful—many people find a dripping faucet very annoying, they get very nervous. It’s nice to hear it in an appreciative way.”[5] Recurring references across his scores to common objects and activities (objects such as suitcases, tables, combs; activities such as moving objects from one place to another, turning things on and off), which you can explore in the Score section of this chapter, amplifies the possibility for events to be discovered coincidentally in one’s everyday environment. Brecht was trained as a research chemist and developed several patents for tampons while working in the personal products division of Johnson and Johnson. Deeply interested in quantum mechanics, Brecht carried over into his artistic practice the viewpoint of physics that our environment is always-already in a state of flux. Overall, Brecht’s event scores are invested in the extraordinary effects of close attention paid to ordinary objects and actions. As his retrospective, self-referential Event Score (1964-65) suggests, such acts of careful observation can extend into the realm of dreams or the unconscious.

Historically, Drip Music marks a hinge moment within the larger history narrated by [Project Title TK]. It is emblematic of the 1960s aesthetic paradigm shift from modernism to postmodernism in its recoding of the strategies of Marcel Duchamp, Jackson Pollock, and John Cage—three major sources for Brecht and his cohort as they began to develop new, experimental practices. Following Duchamp, the event score expands the notion of the readymade to include multi-sensorial events that unfold through space and time. From Pollock, the relationship between the painter and his drip is recast from an indexical, autographic signature into an infinitely renewable procedure that can be materialized in any context, by anyone, and which enables form to emerge via automatic processes. (In 1962, Brecht claimed Pollock’s drip paintings of 1947-51 as performances of Drip Music’s radically simplified second version, “Dripping,” a move that foreshadowed other retroactively designated or readymade Fluxus performances, such as Alison Knowles’s Identical Lunch (1967-75) a habitual meal reframed as a performance piece, featured in chapter TK of this publication.) In the work of Cage, Brecht found different strategies for deploying chance procedures, which he elaborated in the crucial essay “Chance-Imagery,” written in 1957 and published in 1966.[6] In fact, Brecht’s gesture of sending an early draft of this essay to Cage facilitated his first meeting with Cage and Tudor in 1956. (They visited Brecht’s home in New Jersey while on a mushroom-hunting trip.) Relevant here, Cage had already proposed water as an ideal indeterminate material in his compositions Water Music (1952) and Water Walk (1959), the former of which was performed by Tudor alongside some of Brecht’s early scores at Mary Bauermeister’s atelier in Cologne in 1960. In addition to Cagean indeterminacy, Brecht’s notebooks of the period reflect his thinking through Earle Brown’s plays with notational ambiguity in graphic scores such as December 1952. Arguably, Brecht’s event scores combined both notions: they produced an indeterminate outcome arising from the ambiguous, open-ended qualities of written text. Brecht’s quotidian, democratic notational language thus avoided the various limitations introduced by both Cage and Brown’s intimidatingly complicated musical graphics. As Brecht noted in 1959:

The ‘virtu’ of virtuosity must now mean behavior out of one’s life-experience; it cannot be delimited toward physical [or readerly] skill. The listener responding to this sound out of his own experience, adds a new element to the system: composer/notation/performer/sound/listener, and, for himself, defines the sound as music. For the virtuoso listener all sound may be music.”[7]

In terms of distribution, Brecht’s event scores were in many ways a rather private, intimate format. Initially quite diverse in their graphic and material presentation, the artist hand-wrote or typed his scores on pieces of paper and mailed them to other artists, imagining individual works as “little enlightenments I wanted to communicate to my friends who would know what to do with them.”[8] As the Archive section of this chapter shows, Brecht’s scores circulated within music, poetry, and experimental performance circles well before their association with Fluxus. Moreover, ephemera included here shows that Brecht wanted his works published in literary magazines and newspapers such as Kulchur and The Village Voice at the same time they appeared on concert programs at alternative venues like The Living Theatre. Upon the request of Cage, who had witnessed the development of the Brechtian event score (including a 1959 performance of Brecht’s Time-Table Music at Grand Central Station), Brecht sent some of his compositions to Tudor. As a result, they quickly found an international audience in the avant-garde music world. As mentioned previously, Tudor performed Brecht’s Candle-Piece for Radios and Card-Piece for Voice at Bauermeister’s atelier in Cologne, Germany, in 1960. The following year, Tudor presented Incidental Music in 1961 at the Internationale Ferienkurse für Neue Musik in Darmstadt and at the Sogetsu Art Center in Tokyo. Brecht’s correspondence with Tudor, composer Toshi Ichiyanagi, poet M.C. Richards, theater and dance critic Jill Johnston, and Maciunas included in this chapter reveals the scores’ rich, multidisciplinary reception.

From 1962, Brecht’s scores appeared regularly in Fluxus concerts and publications spearheaded by Maciunas, who undertook to design and publish an anthology of Brecht’s scores among the other various anthologies of Fluxus works he diligently prepared. The result of Maciunas and Brecht’s collaboration was Water Yam, a small container in word or cardboard (depending on the edition) that encloses some 70-100 (again, depending on the edition) of Brecht’s scores, printed on loose cards of varying sizes. The publication’s portable, unbound design, which you can browse or search in the Score section of this chapter, accelerates the already active engagement of the reader as he or she orders, rearranges, and interrelates the scores, perhaps even further distributing them. What’s more, the container’s materiality, dimensions, and label, as well as its specific contents, varied across individual copies of Water Yam as they were compiled over the years. The collaborative process whereby Brecht’s event scores are interpreted and performed beyond the artist’s oversight thus threaded through the process of the production and distribution of the scores themselves, as part of the Fluxus publishing program directed by Maciunas, and beyond.

As a notational format positioned between music, poetry, performance, and visual art, the event score proved to be profoundly generative for artists seeking new modes of working beyond established disciplinary or medium specializations from the 1960s onward. Many pathways can be traced through the aftermath of Brecht’s event scores and related forms of neo-avant-garde notation: postminimalism’s concern with process; conceptual art’s engagements with language and the framing of experience; works made all or in part by delegated production; participatory practices that rely upon easily decipherable instructions; and a do-it-yourself ethic that extended to the larger postwar counterculture. The diversity of the event score’s legacies should come as no surprise if we take seriously the words of Cornelius Cardew, a friend to Brecht during his time in London in the late 1960s, who once wrote that Water Yam is best understood as “a course of study, and following on that, a teaching instrument.”[9]

Natilee Harren

Assistant Professor of Contemporary Art History and Critical Studies

University of Houston

Further reading:

-

George Brecht, “Chance-Imagery,” A Great Bear Pamphlet (New York: Something Else Press, 1966). Republished on ubuweb.com, 2004.

-

Anna Dezeuze, “Origins of the Fluxus Score: From Indeterminacy to the ‘Do-It-Yourself’ Artwork,” Performance Research 7, no. 3 (2002): 78-94.

-

Jon Hendricks, Marianne Bech, and Media Farzin, *Fluxus Scores and Instructions: The Transformative Years (Roskilde, Denmark: Museum of Contemporary Art/Detroit: Gilbert and Lila Silverman Fluxus Collection, Detroit, 2008).

-

Liz Kotz, “Post-Cagean Aesthetics and the Event Score,” *Words to Be Looked At: Language in 1960s Art (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2007).

-

John Lely and James Saunders, eds., Word Events: Perspectives on Verbal Notation (London: Continuum, 2012).

-

Michael Nyman, “Part IV: Water Flows and Flux,” Noise, Water, Meat: A History of Sound in the Arts (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1999), 242-288.

-

Julia E. Robinson, “From Abstraction to Model: George Brecht’s Events and the Conceptual Turn in Art of the 1960s,” October 127 (Winter 2009): 77–108.

-

Julia E. Robinson, George Brecht: Events: A Heterospective (Cologne: Walter König, 2005).

George Brecht, notebook of late June 1958, reprinted as George Brecht—Notebooks, vol. 1, June-September 1958, eds. Dieter Daniels and Hermann Braun, (Cologne: Walther König, 1991), p. 4. ↩︎

Michael Nyman, “An Interview with George Brecht” (1976), in An Introduction to George Brecht’s Book of the Tumbler on Fire, by Henry Martin (Milan: Multhipla Edizioni, 1978), 108. ↩︎

Nyman, “An Interview with George Brecht,” 110. ↩︎

George Brecht, quoting George Maciunas in a letter to him, early 1963, George Maciunas correspondence, Hanns Sohm archive, Staatsgalerie Stuttgart. ↩︎

Nyman, “An Interview with George Brecht,” 110. ↩︎

George Brecht, “Chance-Imagery,” A Great Bear Pamphlet (New York: Something Else Press, 1966). Republished on ubuweb.com, 2004. ↩︎

George Brecht, George Brecht—Notebooks, vol. 3, April 1959-August 1959, eds. Dieter Daniels and Hermann Braun (Cologne: Walther König, 1991), 123. ↩︎

George Brecht, “The Origin of Events” (August 1970), in Happenings and Fluxus, eds. Harald Szeemann and Hanns Sohm (Cologne: Kölnischer Kunstverein, 1970), n.p. ↩︎

Cornelius Cardew, concert program notes, Events by George Brecht: Selections from ‘Water YAM,’ Royal Court Theatre, London, 22 November 1970. ↩︎